You asked me: “Why did I love? Why did I live? "

Antanas Sutkus, 2012

RTR Gallery, in collaboration with Agathe Gaillard Gallery, presents "Free Love" an exhibition featuring 45 mainly vintage prints by Jean-Philippe Charbonnier and Antanas Sutkus, two renowned masters of humanist photography.

The photographer is a lover, a brother, a friend. He is filled with love for the other, and the image is both a medium and his message to those he photographs. This is certainly what Sutkus and Charbonnier and defend at the same time, even though, separated by several thousand miles and working in very different settings.

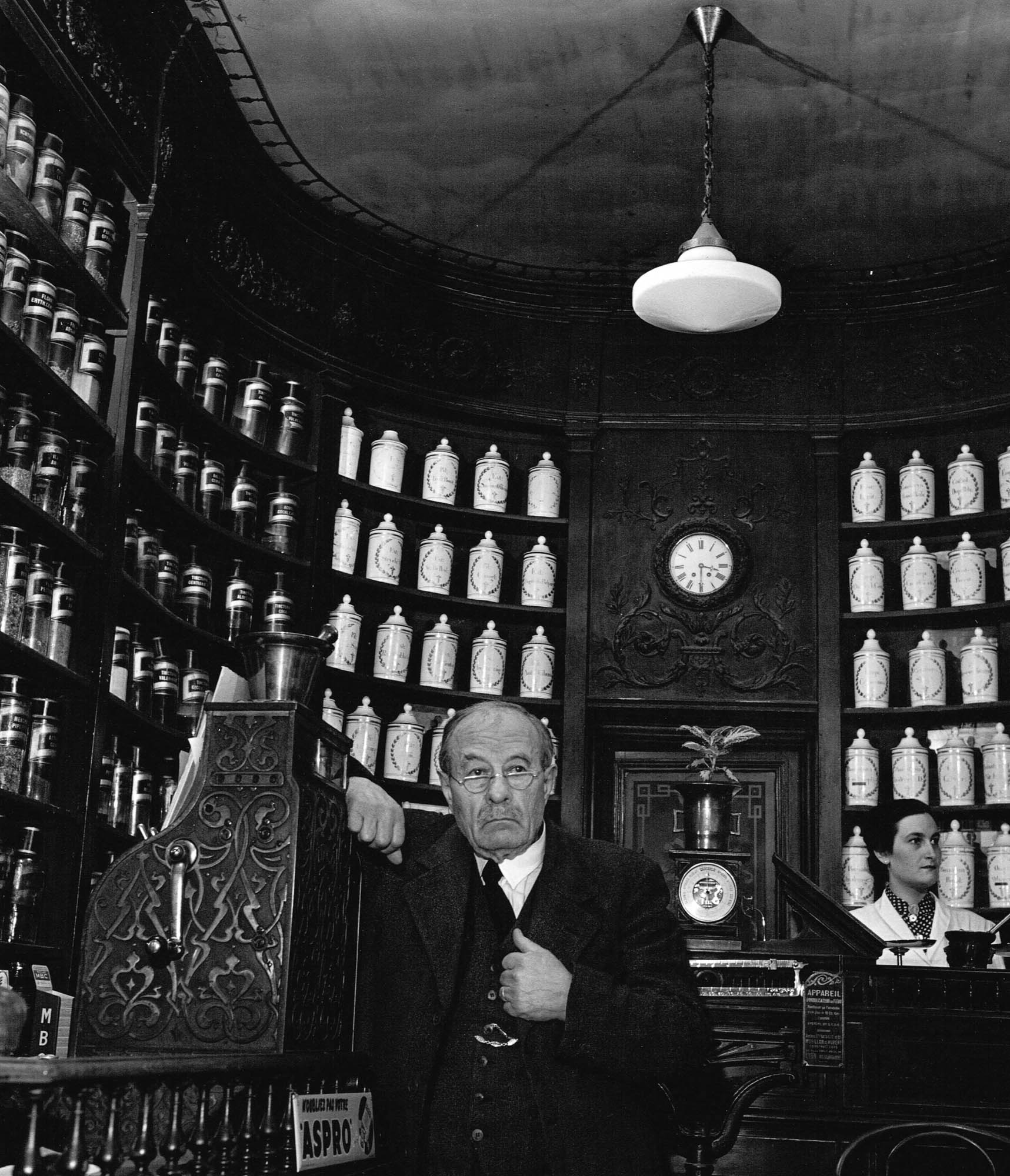

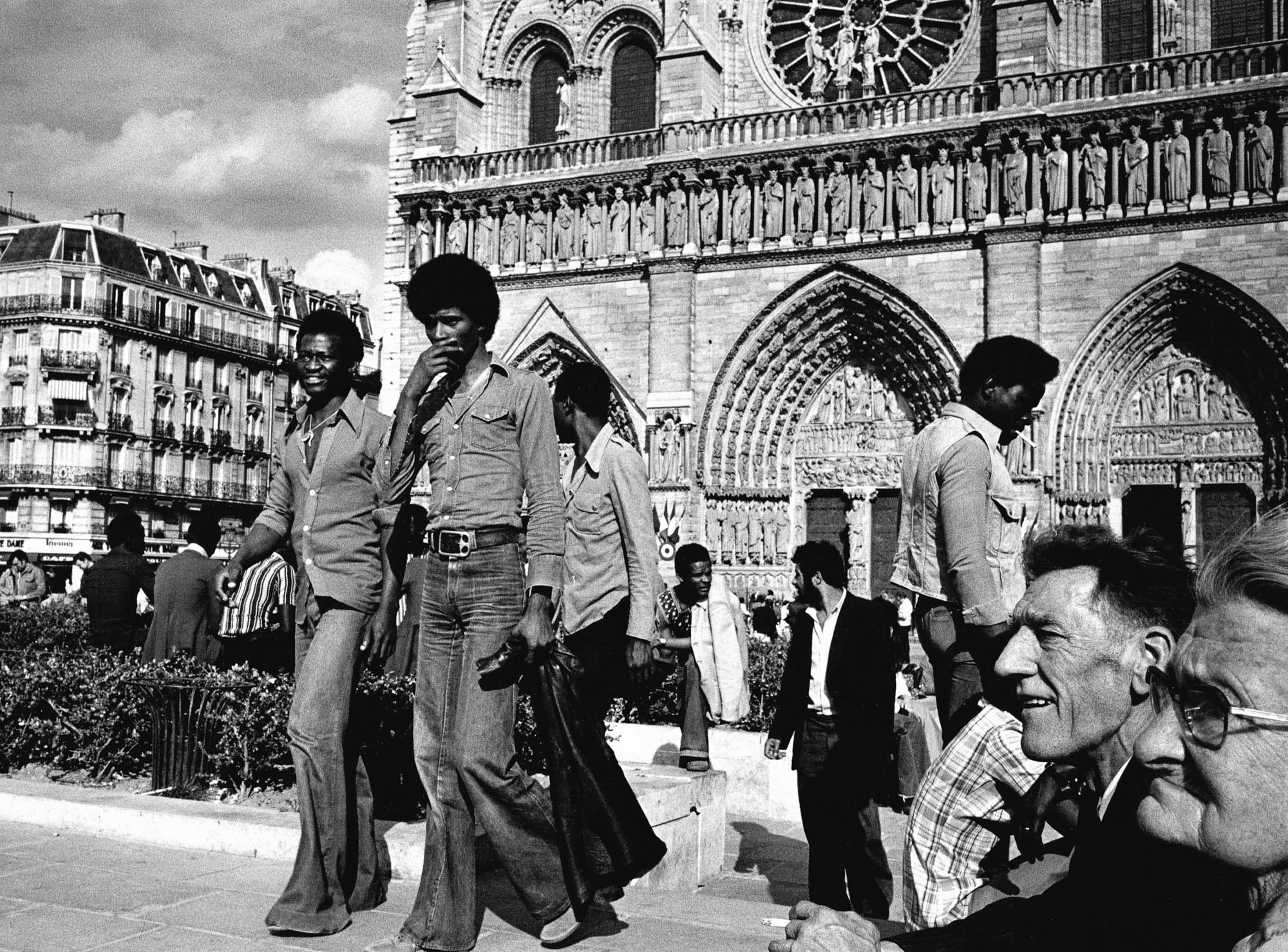

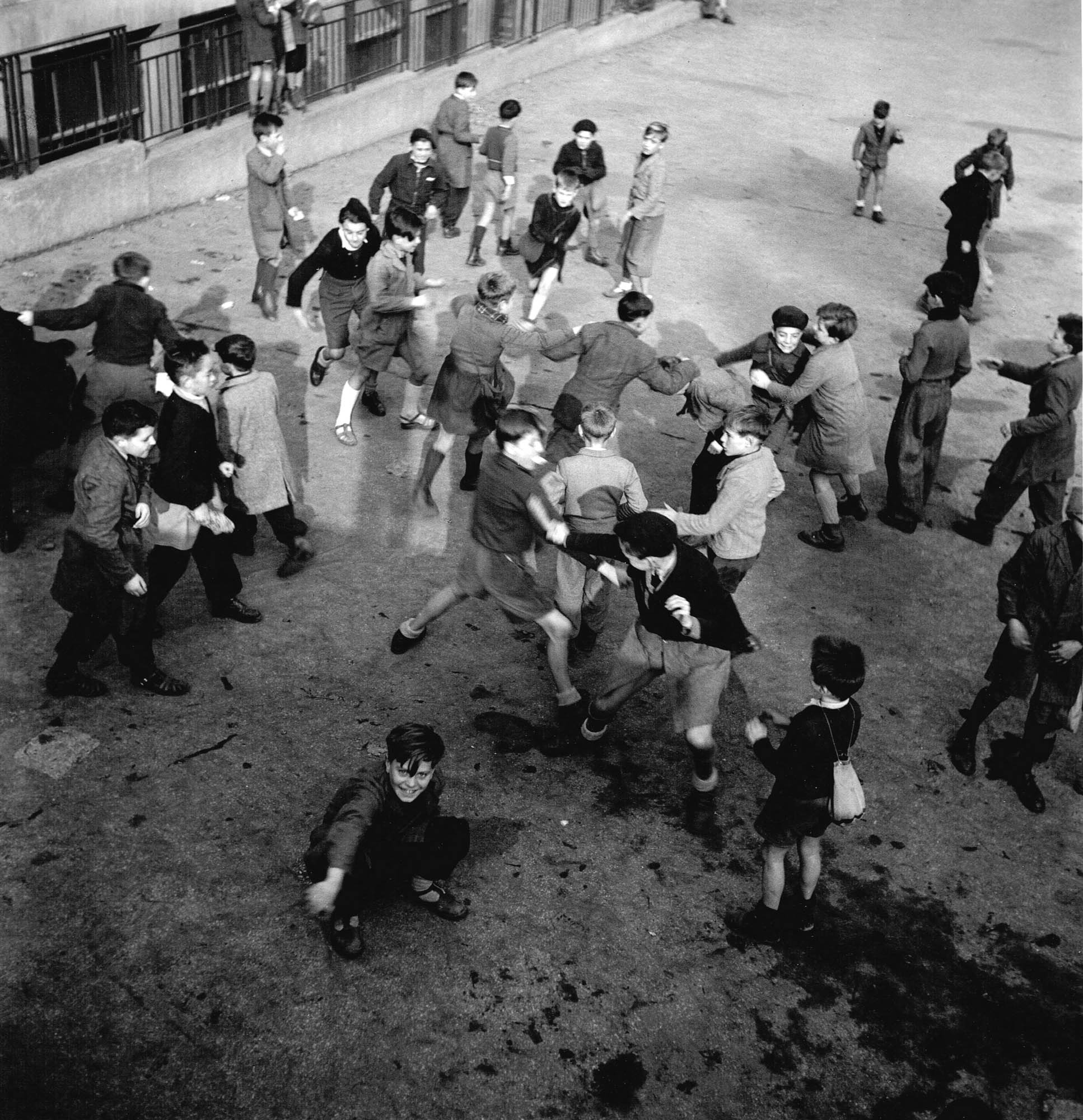

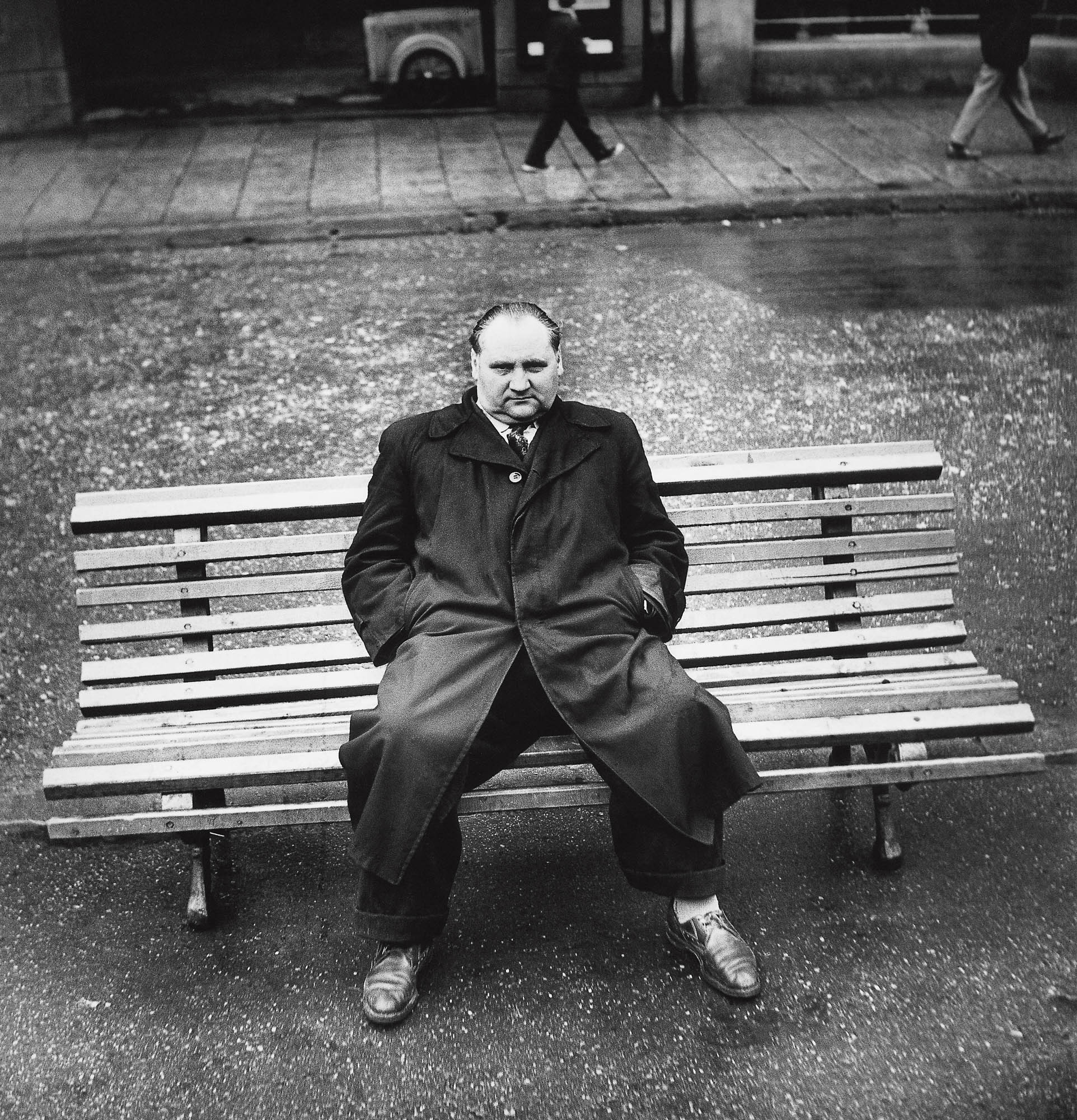

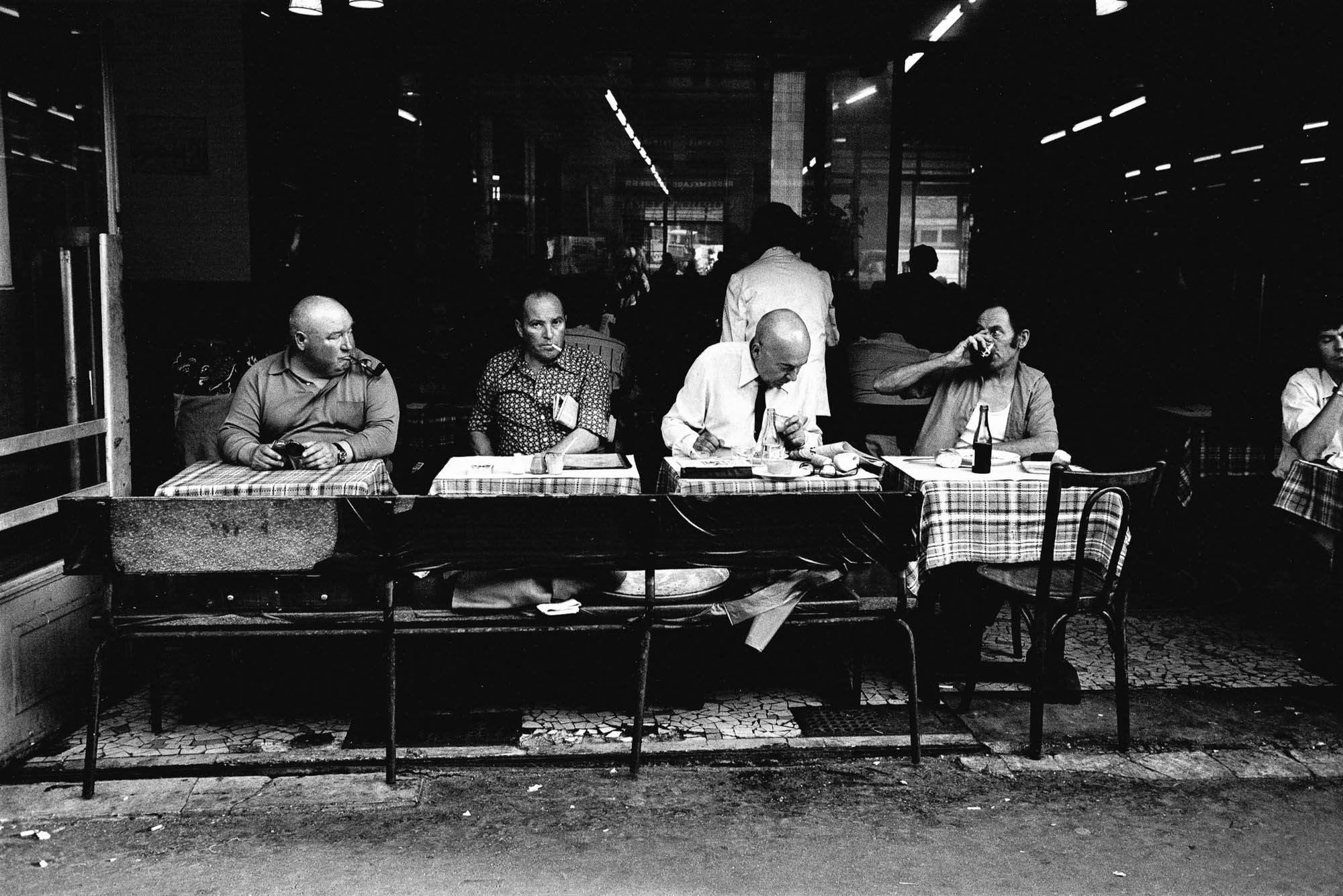

Jean-Philippe Charbonnier was feted during the glories thirties, a fdecade of prosperity alongside Cartier-Bresson, Doisneau, Boubat, Ronis, at a time when French society was profoundly transformed through wealth and we see little by little the disappearance of the world of traditional peasant farmers, the “small people” of pre-War and emergence of the new class of urbanites, educated, middle class or elite in search of pleasure, amusement and levity. The photographer captures small moments, with a look that is often ironic, sometimes tender, resting his gaze on his peers, rich or poor, famous or anonymous. This is not an exercise, he is fully committed to his picture, carefully avoiding value judgment, placing himself beyond conventions or social games: "One makes good picture after several trips after elimination of exoticism, folklorism, the aspect of the "photo turnstile." His photographs seek only the essence of the human and relegating the existential to the background. As one speaks of the eternal feminine, he searches for the eternally human as in: "I think we met before" (name of the first exhibition at Galerie Agathe Gaillard Jean-Philippe Charbonnier, 1974)

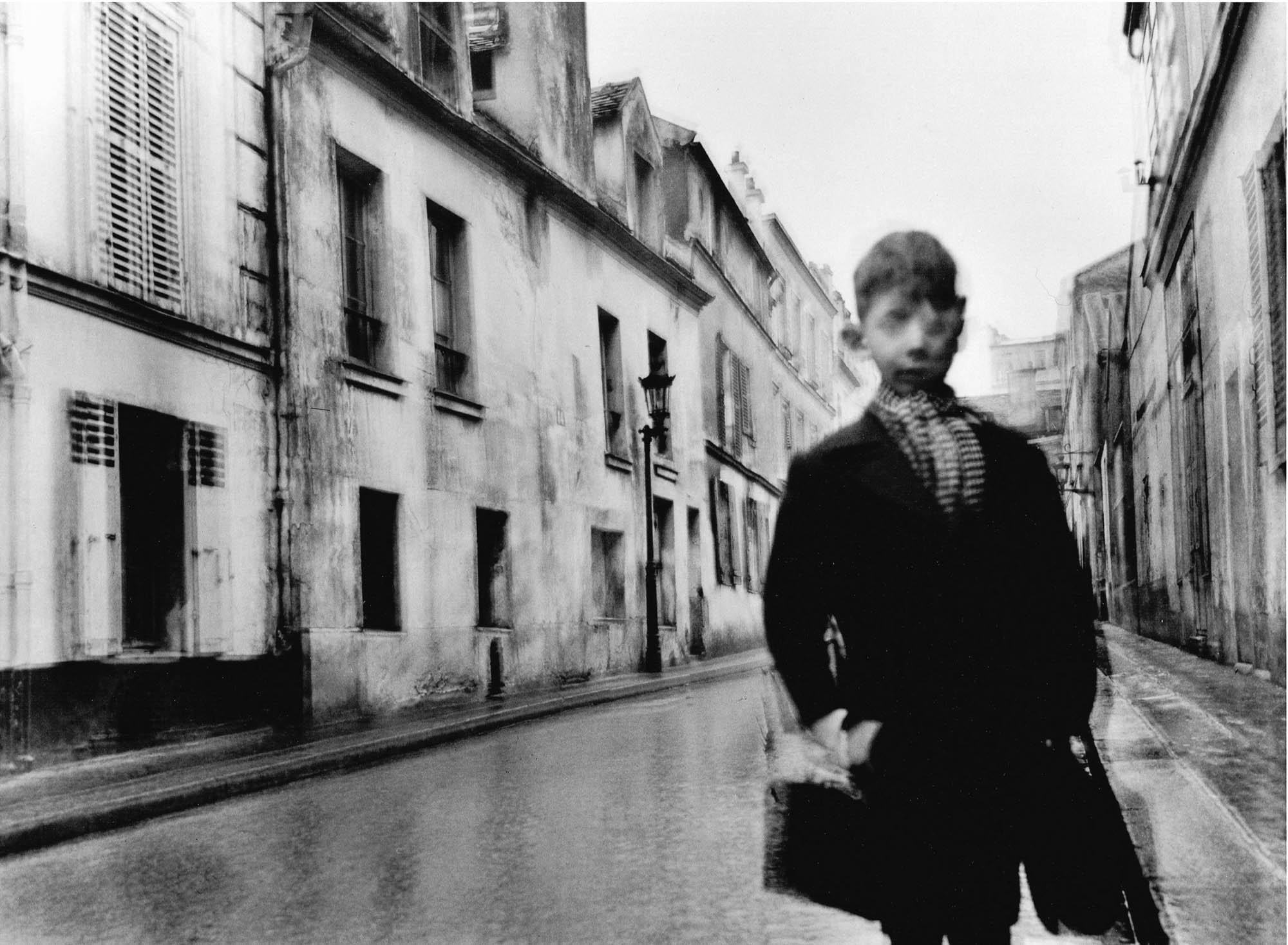

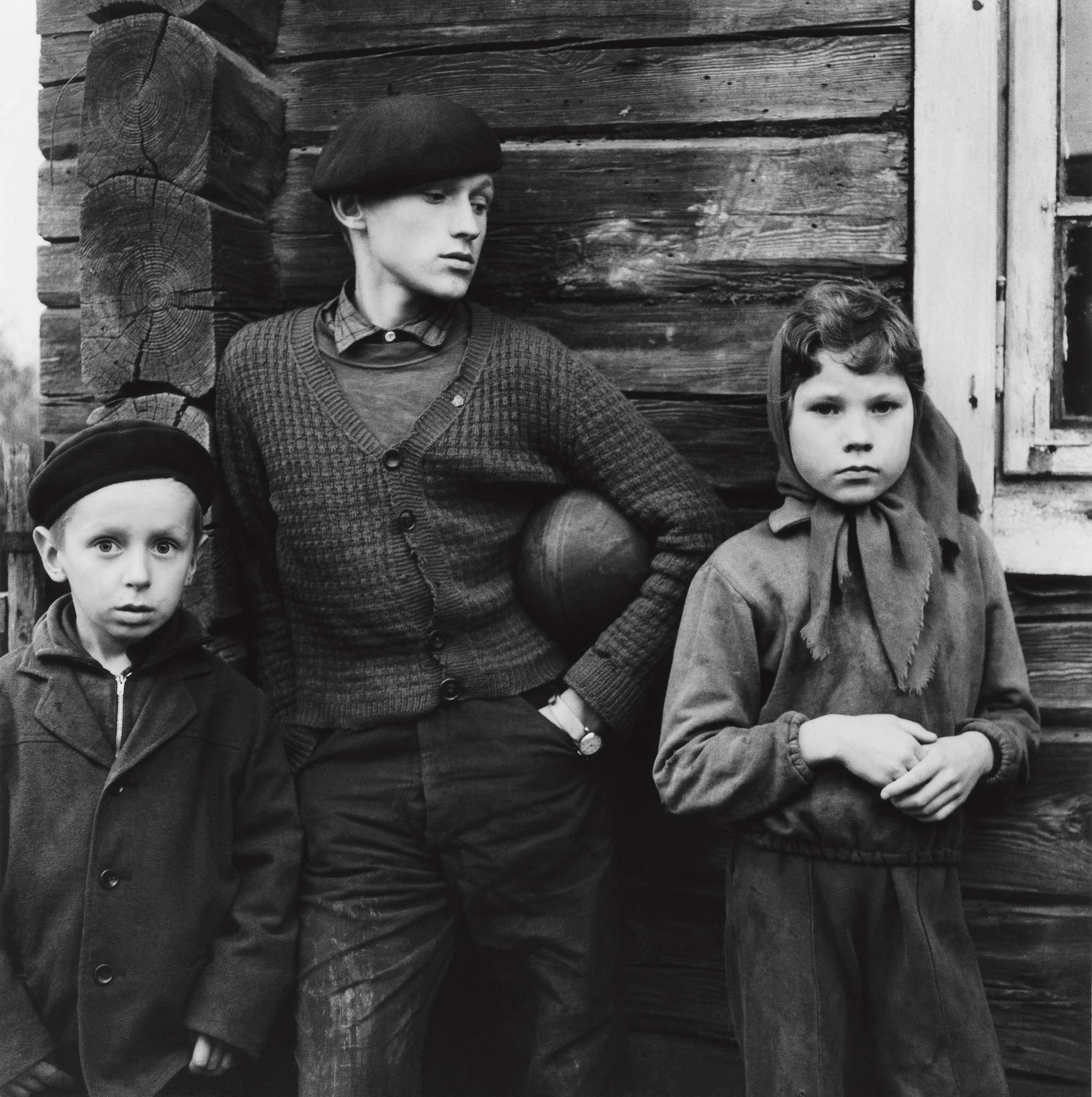

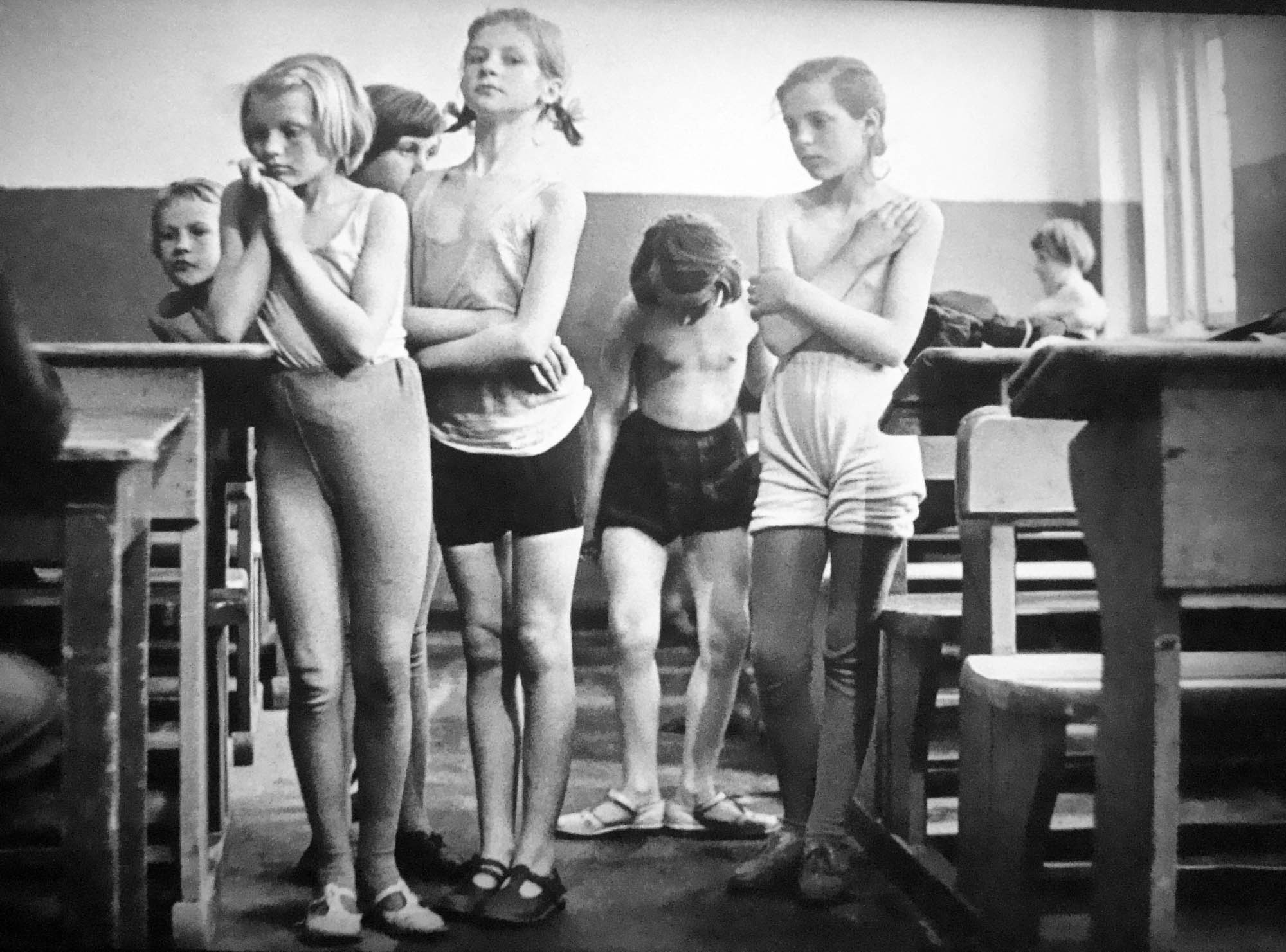

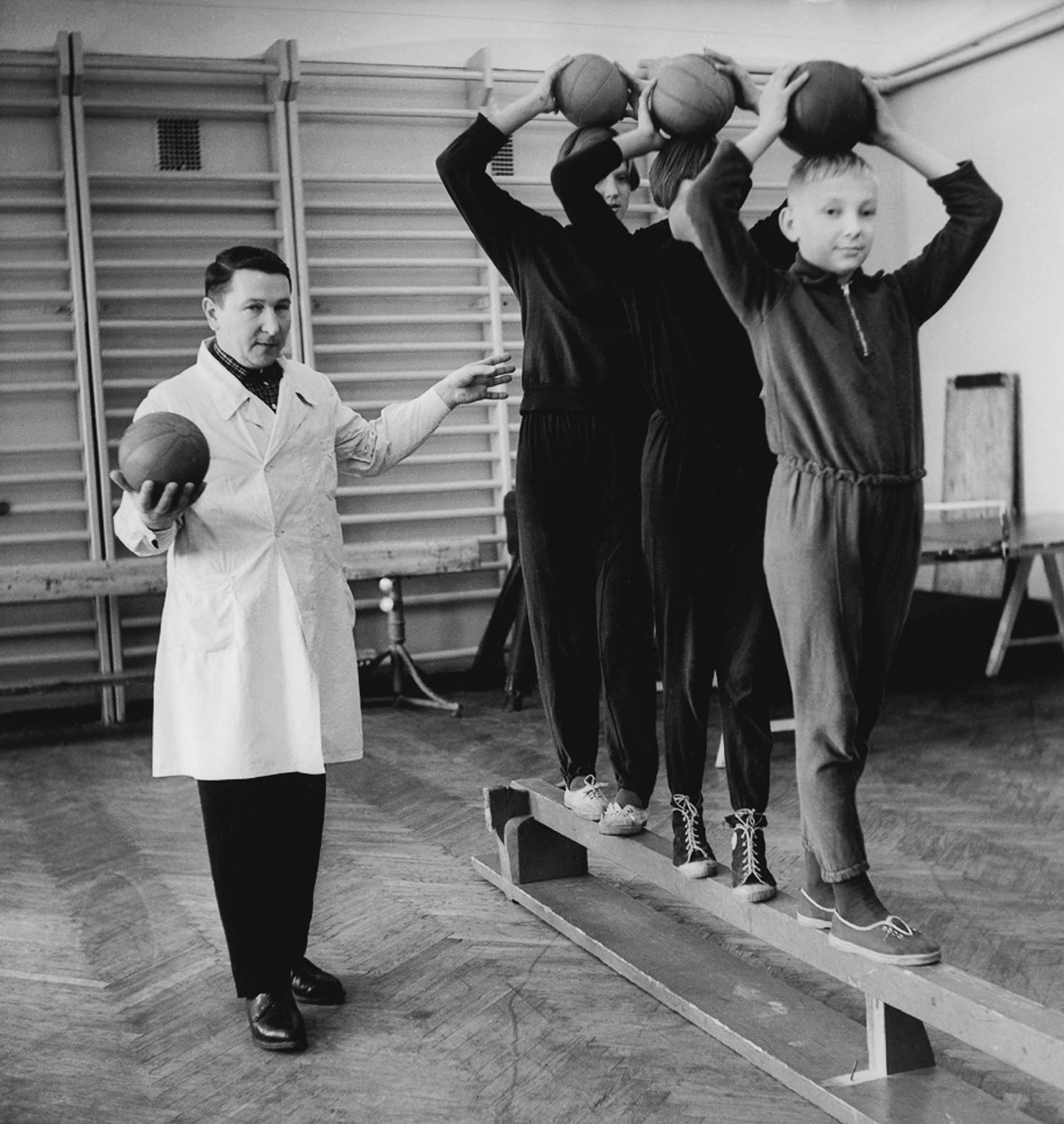

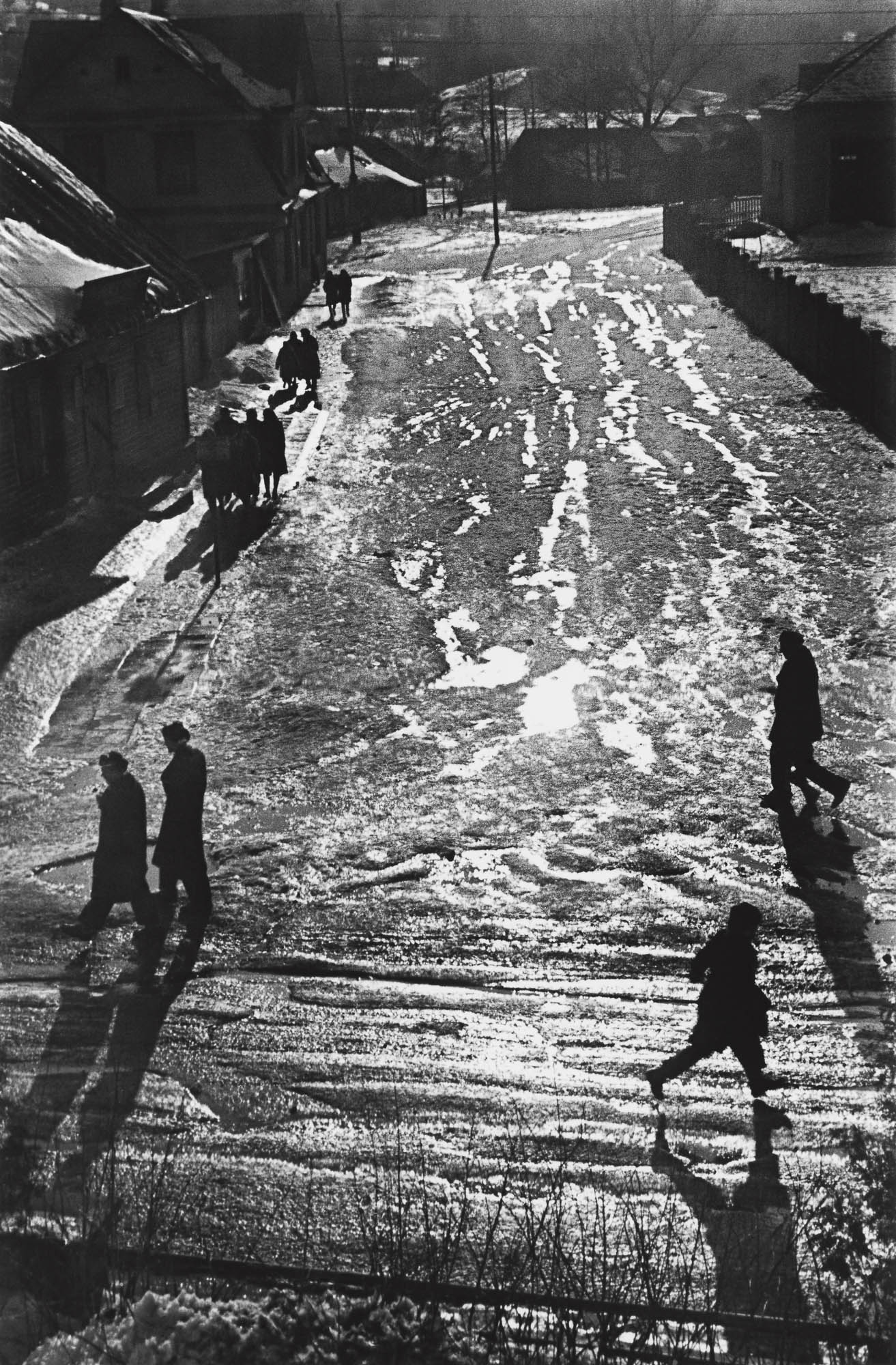

At the same time, Sutkus seeks the essence of the human in a country [Lithuania] engulfed in Sovietism (the Lithuanians call this period the Occupation). His look, his photos are filled with warmth and tenderness for his contemporaries, occasionally touched by humour, the ultimate weapon against totalitarianism. The intention is however not to denounce the regime, which also is rarely featured in the images, but simply to reassert the importance of humanity as a quality and a character trait. Look at these portraits of Sartre at the beginning of the 1960s, visiting a Lithuanian beach, his raincoat inflated by an unexpected gust of wind. He was invited by the authorities of 'brotherly country' who organized this symbolic getaway on the Baltic, and it was Antanas Sutkus, who was chosen to immortalize this propaganda exercise. The result: portrait of a man wandering alone in the dunes and in wind (the sea is invisible), a little worn out, far from his status as The existentialist philosopher.

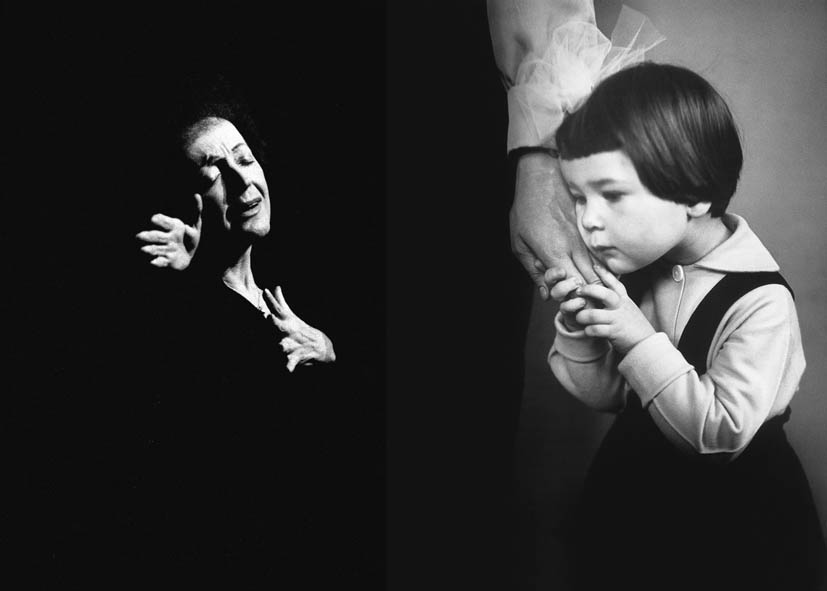

Charbonnier, when confronted with celebrity, also refutes the need to respect the archetype of the public image, on the contrary he sets out searching for what one would call today the intimate person. In this manner he creates a disarming portrait of Piaf, far removed from the official iconography, Bettina is finally brought down from her pedestal of supermodel to be revealed as nothing more than herself, and is made happy by that brief pause/ pose.

"It's the photography who takes photographs," Charbonnier said. Sutkus has the same conviction: "The photo takes itself alone, I am only the instrument." Antanas Sutkus and Jean-Philippe Charbonnier set the photo as a link between individuals, a means of empathy and love of the other, which is essential to achieve freedom, whether in a world that is changing or in a rigid political system.